Photoshop has become a byword for image manipulation in the digital era; enabling anyone to alter the photographs they take. The word itself has become a verb; often with negative overtones. It is the ease in which images can be altered that leads many into questioning the ethics behind such manipulation.

Photography competitions issue strict rules as to how much a photo can be altered, sometimes resulting in winners being disqualified. Advertising has also come under heavy scrutiny in what many people feel is an overuse in Photoshop.

Image manipulation is not new, however. Photo editing existed before Photoshop, and is as old as photography itself. Photo editing before Photoshop included a wide range of techniques, many of them difficult and labour intensive. Airbrushing, paint, double exposure and overlaying separate images were all used. Dye transfers, different contrast papers and different coloured lights used in the enlarger were also popular techniques. A photographer could amend the negative, the print or even the developer depending on the effect desired.

Cut and paste was, at one time, a literal action taken by a photographer. Many well-known Photoshop terms have their origin in darkroom manipulation, including dodging (stopping light reaching an area of paper), burning (increasing the amount of light that reached an area of paper), masking and so on.

The results of these early editing tools are evident in the photography of the 1800’s, ripe for abuse when spiritualism was at its peak. Spirit photographer William H. Mumler’s photographs featured bereaved sitters flanked by ghostly apparitions. One of these features widowed Mary Todd; the ghost of Abraham Lincoln standing behind her.

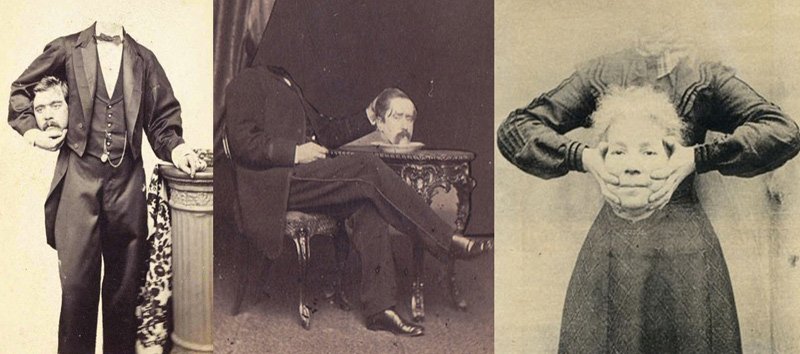

Double-exposure was also featured in many Victorian images to create doppelgangers and ‘headless’ men and women. Later, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths drew notoriety and fooled a large number of people with their cardboard figures of fairies.

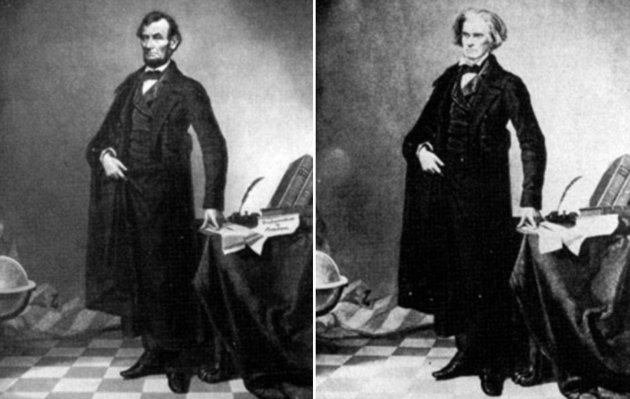

Photo composites were also used often. Abraham Lincoln was altered again; this time, his head was placed on the body of politician John Calhorn. A portrait of Ulysses S. Grant was comprised of three separate photographs.

Do these photographs depict reality? Do they in fact depict their subjects as they truly are? What is it about photography that insists on the real?

The debates around ethics in manipulation are linked to how much one considers photography the act of capturing an objective reality. In the early days of photography, people were overwhelmed by the realism captured by this new invention. As photographic technology advanced, cameras became mobile and exposure times were reduced. Stilted poses were replaced by candid snapshots. Its novel immediacy gave way to the myth of the all-seeing, objective eye of the camera.

Yet image alterations were always required. Manipulation was required to get the image closer to a reality that the photographer was aiming for, but did not capture. Scratches, lens flairs and image compression were considered alterable components of a captured image.

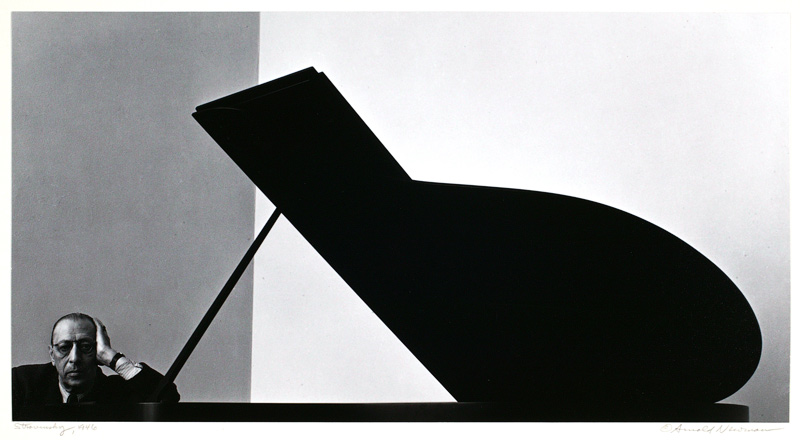

But photo editing does not just mean doctoring or retouching an image. Editing takes place at every point during a photograph’s inception. Portrait photographer Arnold Newman valued the practice of cropping in his works, making definite decisions as to where the edges of his photographs occurred.

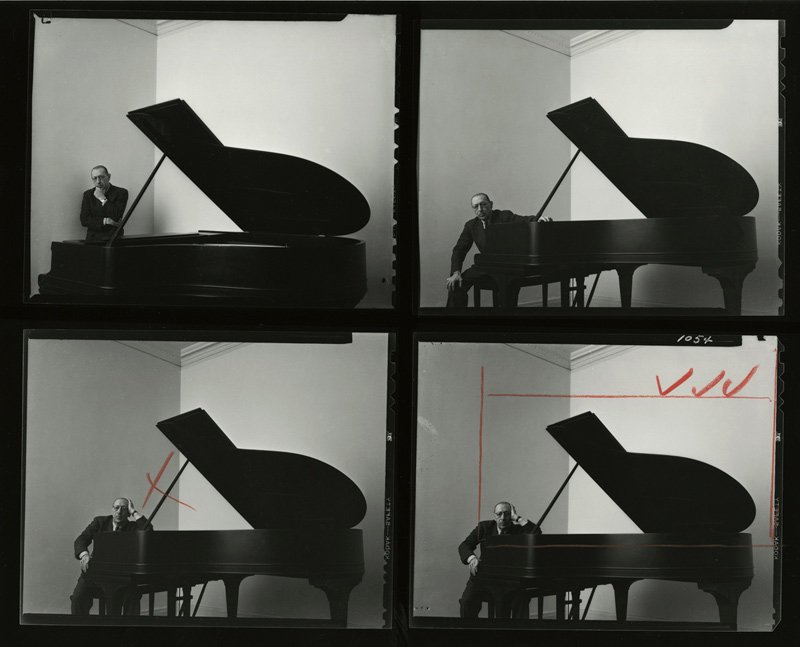

Newman’s famous photograph of Igor Stravinsky is a powerful image. Yet it is not the exact image Newman captured. A contact sheet of four negatives, featuring Igor Stravinsky, show how Newman made clear decisions as to what to include and not include in his final image.

The process of photography comprises a wealth of small decisions that are unique to each photographer themselves; image selection, cropping, choosing what to include and exclude. The photographer made the decision of which lens to use, which film speed, what to photograph, at which time to take the photo itself. These are all options open to the photographer in camera. After, if several images are taken, a decision is made as to which one will be chosen. Yet, they are all of the same subject, the same ‘reality’. It seems then that some are more ‘real’ than others.

As with Arnold Newman’s portraits, these photographs appear to show their sitters caught in the middle of them at work, yet that is not the fact. The shots were carefully set up and orchestrated. Newman made the decision to eschew the studio and capture his subjects in their own environments. Yet does this in any way affect the ‘truth’ Newman was after?

Artistic intention is evident right from the very beginning, and manipulation is a very part of photography itself. So, can we ever say that any photograph depicts reality as it is? What is it we are trying to capture? Does reality exist in art, and has photography ever been objective?

Make up and clothing can change our appearance. But does it change our reality? Perhaps this gives us a clue as to how to think about editing photography. People often use makeup and clothing to express themselves. As so with editing photographs; each decision made is an artistic decision and speaks to the message we are trying to communicate.

The lines between acceptable and unacceptable are often blurred. When our message is to deceive, this can cause trouble when our photography is featured in arenas where honesty is paramount. Where photojournalism and documentary is concerned, we ought to be objective. But is this ever possible?

Where is the line between truth and reality? These are questions that affect every artist. Perhaps photography represents not a reality but the truth of the photographer, which was very different in the world of photo editing before photoshop.

Leave A Comment