Welcome Photoion students and photography fans. We’ve got a special treat for you today; an exclusive interview with Pete Pin.

Pete is a Cambodian American artist whose work exploring Cambodian Americans lives after the Killing Fields is as fascinating as it is powerful.

We sat down with Pete to ask him about how he got into photography, his process, and his project Cambodian Diaspora.

Pete Pin

Hi Pete, why photography? (Why is it your medium? How did you get passionate? When did you start? Why do you stick with it, etc.)

I purchased my first camera in the summer of 2008, right before entering a PhD program in the Political Science department at Berkeley. At that point, I had wanted to pursue a career in academia. My first real engagement with photography occurred months later at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, where they had two simultaneous photography exhibitions: a Richard Avedon retrospective, and the 50th Anniversary exhibition of Robert Frank’s The Americans. Prior to this, I had absolutely no understanding of photography as a medium of visual expression.

I purchased my first camera in the summer of 2008, right before entering a PhD program in the Political Science department at Berkeley. At that point, I had wanted to pursue a career in academia. My first real engagement with photography occurred months later at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, where they had two simultaneous photography exhibitions: a Richard Avedon retrospective, and the 50th Anniversary exhibition of Robert Frank’s The Americans. Prior to this, I had absolutely no understanding of photography as a medium of visual expression.

I really studied both photographers, returning to the SF MOMA weekly. What was incredible about the Robert Frank exhibition in particular was its depth; every frame and sequence was examined in detail. I learned for the first time, through my obsession with these exhibitions, the language of photography. Through Avedon and Frank, I became fascinated with both portraiture and reportage.

At Berkeley, I became increasingly disillusioned with my studies and found myself spending more time thinking about photography. I started hanging out with a lot of street kids, train hoppers, and squatters, and before long I started photographing them. I purchased a single strobe light, some light stands, etc., and set up a makeshift portrait studio in the basement of the Cooperative I was living in, and taught myself portraiture by photographing the punk kids I was hanging out with. Shortly after this, I took a “leave of absence” from my studies, and moved to New York to pursue “photography” full-time.

What is a photographer? (what’s his/her role as well)

A photographer is someone who uses the visual language of photography to communicate. Everyone laments about the explosion of cameras among the public, via smartphones etc., and the supposed “death” of photography. I believe this is shortsighted and misses the point entirely, specifically if we parse out my very basic definition of a photographer. Mass literacy did not kill writing; it had the opposite effect by both enlarging the audience and the pool of “professional writers.” It is the same with photography. As photography becomes more and more ingrained in everyday modern life, there is a newfound opportunity to engage wider audiences, and increase visual literacy. The role of the photographer now, more than ever, is to use this visual language to provoke, inform, and inspire their audience through compelling visual storytelling.

What’s your best advice to somebody that wants to become a photographer today?

Find something that moves you, a story that you HAVE to tell, and that can only be told in your unique voice, informed by your own personal connection to it.

The kind of photography – and by extension – photographer, that moves me personally is deeply intentional, personal projects that explore complex themes and ideas, and are multidimensional in both project design and audience engagement.

Now more than ever, photography is not an island; simply taking photos is not enough. If we understand that photography is, at its most basic, visual communication, we need to be far more critical in how we devise our audience engagement strategy.

This is, in my opinion, more important than the time you spend behind the camera. New media – the web and mobile phones – provide newfound opportunities for compelling visual storytelling and outreach.

However, when thinking of project design and outreach, let it come naturally, let the needs of the project dictate your process and engagement strategy. Everything needs to be intentional, from the way you approach the very process of how you photograph, to the tools you use for distribution and outreach.

Finally, be prepared to wear many, many, different hats, and embrace this whole-heartedly.

Can you talk about your project “Cambodian Diaspora”?

I was born in a refugee camp on the border of Cambodia and Thailand after the Killing Fields in Cambodia, to parents who spent the formative years of their youth in a Khmer Rouge labor camp. My family, along with most Cambodian families at the time, lost the entirety of their worldly belongings. We emmigrated to the States as refugees when I was an infant, to Stockton, CA. Growing up, without fully understanding that history, I witnessed, in my own personal life and the wider refugee community, the aftermath of that legacy in the form of structural poverty and violence.

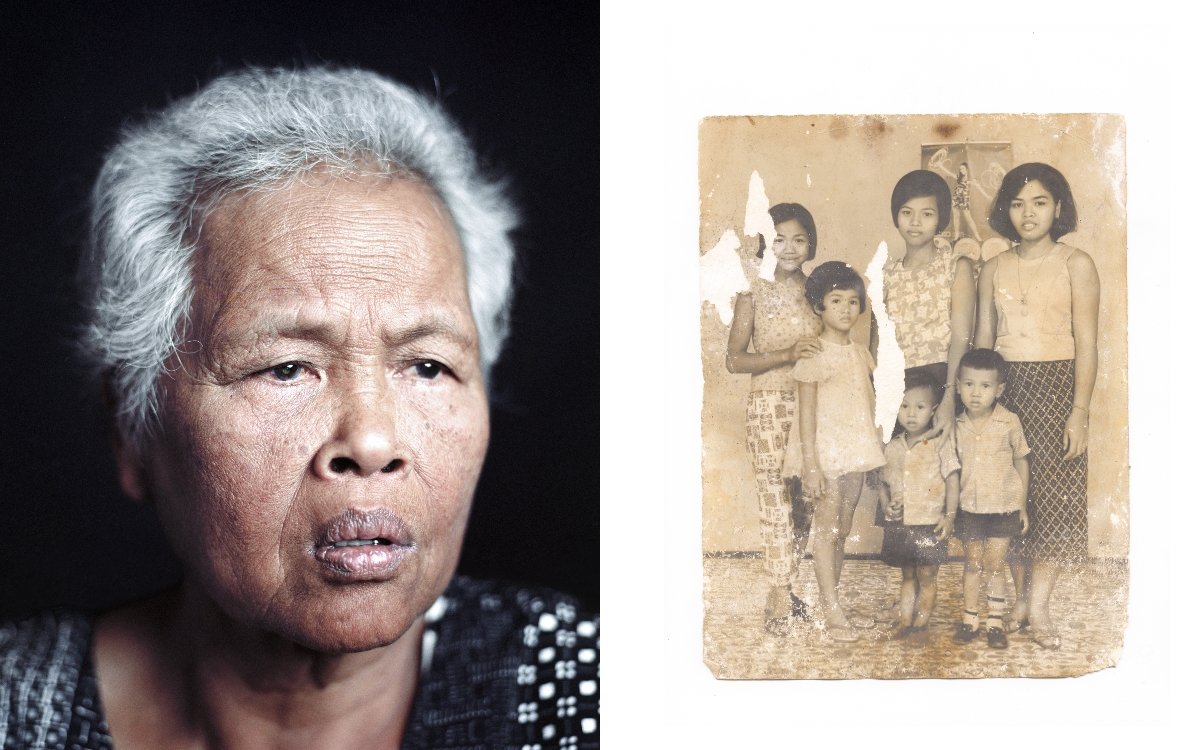

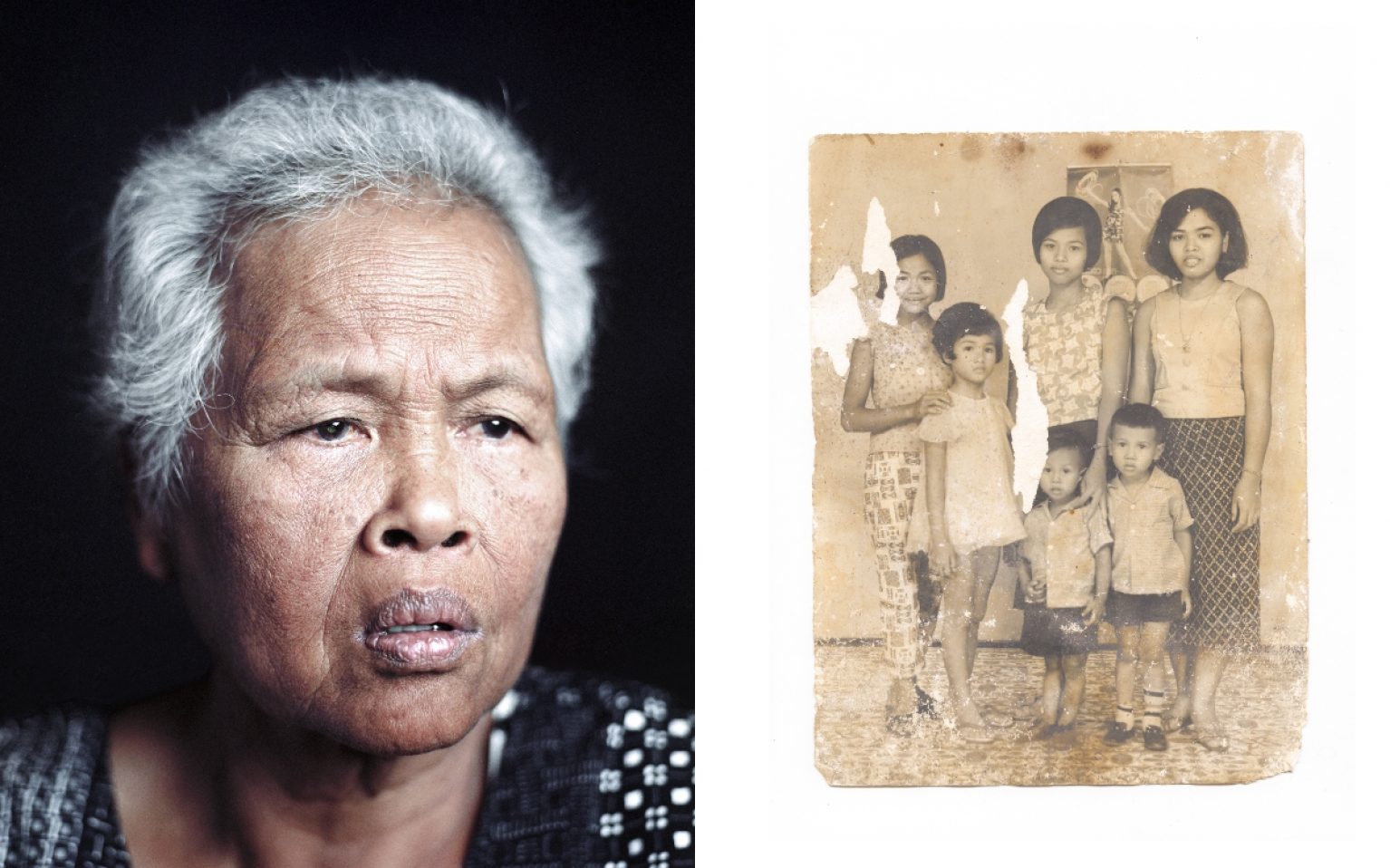

In the fall of 2010, I set up a makeshift portrait studio in my grandmother’s garage in Stockton, California. Right before I took her photo, she recounted to me the heartbreaking details of my family’s experience during the genocide for the first time in her life. As she spoke, I was overcome with a sense of history and a connection to a past that had for so long been withheld from me.

From that initial conversation, I learned that a family portrait, taken before the revolution, was among one of my families only possessions saved from before the war. Buried during the revolution, it was retrieved and brought over by an uncle to America. I understood instinctively the significance of that portrait, not as a photograph, but as a tangible, material connection that my family had to their former lives in Cambodia.

Informed by the experience of photographing and interviewing my grandmother, for nearly four years I have been photographing in Cambodian American communities across the country, building a visual narrative of the Cambodian American experience.

Through this work, I have learned that the very process of photographing and documenting my own community gave me insights to my own identity and relationship to the legacy that I have inherited; most importantly it empowered me to become a guardian of my own family story. With this realization, my understanding of the power and implications of photography and visual storytelling has shifted dramatically. No longer content with just documenting and photographing, I have been exploring how to employ visual narrative and storytelling to create space for generational dialogue.

Bunthoeun Kann, 29, aka T-Money, who was born in a refugee camp, shows his gunshot wounds from a Cambodian gang member who fired on a crowd of Cambodian teenagers in the parking lot of a Denny’s following their prom. He was shot five times. Long Beach, California. March 2011 (c) Pete Pin

Over the years, this has iterated through various forms of community engagement. I have done installations in Cambodian American communities: in the basements of Cambodian American homes, in community centers, and most recently a mental health clinic that has treated Cambodian Americans for PTSD. I have also experimented with workshops with Cambodian American youth, using my photographs as a focal point of personal reflection.

I have integrated my own personal insights to my process of photographing with the understanding that it can generate a literal space for dialogue among the very family I am photographing. This has materialized most poignantly in a series of diptych portraits of Cambodian elders that speak about memory.

Produced on location in the living rooms of Cambodian Americans, these diptych’s combine a portrait with archival scans of documents and photographs saved from before the war or during stays in refugee camps. Having lost all of their worldly belongings, these pictures are the only tangible, material bridge that connects the past with the present.

Done in partnership with other young Cambodian Americans, who enlist their parents and family members to participate and are present during the session, the production of these diptych’s have the power to create inter-generational dialogue naturally in the physicality of family space. I have witnessed on multiple occasions the telling of untold stories among families,

instigated through the act of collectively looking for and viewing this ephemera.

Neighborhood adjacent to the ‘Ditch,’ a focal point of gang violence, Long Beach, California, March 2011 (c) Pete Pin

Building on this, I am currently working on producing a mobile/web based interactive that aims to bridge the generational gap by focusing on intergenerational dialogue via storytelling, centered around these memories saved from before the war and/or during stays in refugee camps. Specifically, the platform will prompt young Cambodians to find, photograph, and share these moments.

What’s the main difference in your opinion between writing and photography?

I like to think that there are as many similarities as there are differences. And I think this is important to note. Like writing, there’s a huge spectrum in the language of photography. My partner is a fiction writer and journalist who writes frequently about creativity. We inform each other respectively, in regards to process. On a project level, we both spend way more time working on grants, sending out statements, and crafting pitches than we do actually writing or photographing.

I always considered myself a better writer than a photographer. As mentioned earlier, photography came much later in my life. But my love for literature has informed my understanding of photography.

Great writing obviously reads effortlessly. But every word is crafted, every bit is labored. This is the same with photography, specifically in how we choose to sequence our images, and how we choose to engage our audiences. We incorporate visual metaphors, emotional tone, thematic structure, and pacing like a piece of poetry.

Why and how did you decide to use also found photographs in your projects?

As mentioned above, this came naturally, through the needs of my project. I treat my flatbed scanner, which I carry on location, like a camera. These found photographs are generational bridges to the past and a focal point of inter-generational dialogue.

Left photo: Portrait of Pete’s grandmother, Stockton, CA. The Cambodian Diaspora, (c) Pete Pin 2010; Right photo: Family portrait pre-revolution, one of only two family possessions saved by his family from before the Killing Fields, Cambodia 1972

Would you read us a page of your diary? (if you don’t keep one, would you pretend for us? sort of a day in the life of Pete)

I no longer keep a diary, so this is a condensed schedule of my day today. This morning, I am finishing two quick email interviews, this one, in addition to an interview about Cambodian American artists. After that, I will work on outreach in the Cambodian American community for a show opening this week. This involves reaching out to media contacts and sending a pitch. Following that, I will be working on a proposal for a proposed pilot residency with the New York Public Library and the Magnum Foundation for this summer. This entails further honing in project design and, of course, funding. If there’s enough time in the day, I will also be working on a grant for the audience engagement portion of my project. Finally, at 7pm, I log on to my “day” job as a freelance photo editor at TIME.com, working remotely from my office at home.

What do you see in your future?

I would like to continue to develop Cambodian Diaspora, iterating the project design and audience engagement. I am currently seeking funding for the interactive component of this project. If this is successful, I would like to develop a dynamic community installation that incorporates the new technology that I hope to develop (real-time social media integration with visual design).

Moving beyond this, I hope to travel to Cambodia and pursue an entirely different project all together, focusing on the legacy of the Killing Fields on the broader development of the country, which is what I was initially interested in pursuing in graduate school before finding photography.

In the Fall of this year, I will start co-teaching an exciting class at the New School in New York on the Cambodian American experience. This is another extension of outreach. Beyond this, I hope to have the opportunity to explore further teaching options.

Leave A Comment