We’re delighted to announce that a new tutor has joined the PhotoIon School:

Giulia Bianchi is a documentary photographer and photo editor specialized in portraiture, storytelling and book making. Her work has been published in The Guardian, TIME, La Repubblica, other magazines and books, and has been internationally exhibited.

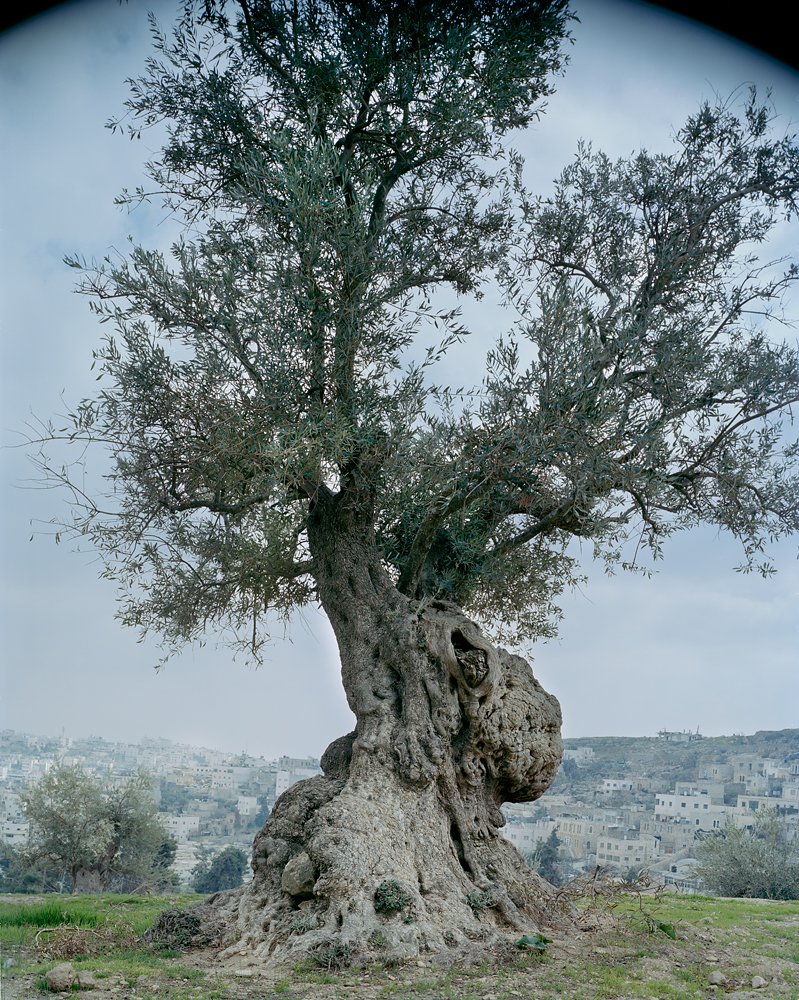

(Photo: 6th February 2014, Hebron, a territory disputed between Palestine and Israel. Giulia is making large format photographs of ancient olive trees.)

Giulia Bianchi

She attended the well known PJ program of The International Center Of Photography in New York City, but managed to develop beyond the strict confines of photojournalism and find her own path of image making. She also attended the New York Art Students League to study oil painting and sculpture and she also studied philosophy, feminism and aesthetics at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research.

Giulia’s work speaks of the best kind of restlessness a person can have: deep curiosity about people and their idiosyncrasies, and willingness to consider multiple facets of any question. She continued her long-format documentary practice, with an immensely moving project about Catholic Women Priests who have been ex-communicated by the Vatican, despite their spirituality and commitment to the church. Also, she embarked on complex and ambitious collaborative projects involving many different types of image-making procedures, poetry and memoir.

The dreams and symbols she encounters have become a strong element in this powerful and evolving body of work. Giulia is a keen researcher. People are drawn to Giulia’s enthusiasm and determination, so much that she can go into very unfamiliar territory and gain the trust of the people she approaches: for her last project, Giulia spent 6 months traveling among Egypt, Palestine and Israeli’s settlements.

We interviewed Giulia on May 27th 2014.

Hi Giulia! Why Photography?

Photography is the medium that forced me and educated me to critically analyze the shapes and appearances of reality, and organize them in stories.

I’m especially interested in the relationship between the machine and reality: a camera is a tool that, differently from a drawing, allows me to capture very fast something very close to what I see.

If I don’t see something I can’t draw it, but if I don’t notice something in a photograph, the camera is still recording it.

I photograph what I want to understand, looking for new thoughts through the analysis of images that, at least for a second, have been real and alive in my world.

Then I’ll start a process of re-elaboration through writing and painting.

Can you talk about your last project?

There is a space, psychological, in those who have firmly believed in God when they were children, and than have lost their faith later, embracing a dichotomy of science and religion, tradition and modernity.

That lacuna, that was occupied by the love for God, still exists, orphan but intact in their minds.

There is another space, geographical, an area where the important monotheistic religions have been witnessing a millenary dialogue with God and His Prophets: these are the lands of Israel, West Bank and the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt. Today these territories, which are disputed between Palestinians and Israelis, Muslims and Jews, are synonymous with Apartheid, conflicted and unnatural landscapes.

It’s where these two spaces, one psychological and the other geographical, meet each other, that birthed the book I’m realizing. It’s titled “Thou Shalt Not Tempt the Lord thy God, A Lesser Geography of the Holy Land”

It’s a journey that takes place in the strangest, but most intimate of all the places: the space between the God that fled away and the One that maybe will come at last.

It’s a play of coincidences, a continuous exchange of symbols, chasing my dreams, facing the risk to surrender to my own subjectivity: looking for myself more than the meaning of God, enriching my own judgment more than a curious open empathy for different lives.

Read us a page of your Diary:

Hebron, February 6 2014.

——

We went.

Here people move hitchhiking, showing the same entitlement we would taking a public bus . Sometimes not even “hello” or “thanks” are said to the silent drivers that lead the settlers up and down from Kyriat Arba to the Tomb of the Patriarchs.

From there, we stroll in front of three different checkpoints (yesterday one threw gas bombs towards Palestinians riots) inside the famous ghost district, that in 1929 saw the massacre of 70 Jews and the escape of hundreds performed by Arabs.

Since that moment it belonged to the Kasbah**, until a radical Israeli settler shot dead 29 Palestinian worshippers at Hebron’s Ibrahimi mosque in 1994, and it was emptied by the Israeli Army that feared revenge against its own citizens.

Today, Shuhada Street still presents only shut down shops with locked doors.

There is a narrow road that goes parallel to the Arab cemetery, it leads to the spring of Abraham on top of the hill and from there goes to the ruins of what, 3000 years ago, was the Hebrew fortress of Hevron. All around are the remains of old and crumbling walls and hundreds of olive trees the width of a car.

They are twisted, sometimes emptied, gnarled, with giant round excrescences that emerge from their bodies that have become a mixture of stones and bark. But they are still alive. Majestic.

I feel happy.

Despite the tension that I’ve been feeling since I arrived 5 months ago.

I said many times that I’m not working on a political book, that I’m interested in the Holy Land, but at every corner and in front of every cup of tea I was asked to be a judge and a sided witness of their own narrative about the conflict.

I’ve been presented excruciating, bleeding stories by both Israelis and Palestinians.

I’ve been loved by people before and after the checkpoints.

I want to be life giving like these olive trees.

I take the view camera and I start watching observing them through the Fresnel glass. From a distance first, then close up, from the top, then down, I turn the lens and use its limitations to darken a little piece of sky as if a storm was coming, obscuring the azure. I focus on a cut, a stone, a root.

I focus on the bark, while the leaves are open blurred against the sky.

I feel happy, I feel like Sally Mann.

I begin to understand my camera and I understand why I use it: until I photograph it, I’ve never really seen a tree before. It’s on the Fresnel glass that reality emerges for the first time as bright, alive and present.

The Fresnel glass, showing the world upside down, it’s more real than reality. It’s romantic, melancholic, dreamy, and spiritual.

With my digital camera, I always tried to imitate what

others do with the view camera. With the view camera now I realize that I don’t have time to imitate anyone. It’s the image that guides me, it’s the world that decides how it wants to be photographed by me, and so the camera twists on a twisted tripod, focusing crosswise details, looking up than down and never leveled, never cold.

Looking through the Fresnel glass frees me of all the images I’ve seen so far in my life in order to create new ones. As with the oil painting where the artist continues to move and change colors until they make sense in his mind, so I continue to move my lens, my focus, my perspective, and than the front and the back of the camera, I keep moving it as long as the image makes sense to my soul.

And suddenly it appears, like seeing myself in that tree, like seeing one of my dreams.

My heart beats faster, like the one of a lover.

Giulia

* Kyriat Arba: Israeli settlement in Palestine, within the Palestinian city of Hebron.

** Kasbah: Arab market.

—

Featured Image: courtesy of Michael Craig Palmer

Other Images: photos by Giulia Bianchi, work in progress “A Lesser Geography of the Holy Land”

[…] Our New tutor Giulia Bianchi. We are so excited to have a new member of our team! Read more […]

[…] The Curious Story of Julia Cameron, one of the earliest portrait photographers!Read more […]

[…] Read more […]

[…] Our New tutor Giulia Bianchi. We are so excited to have a new member of our team! Read more […]